By JACK ROSSI

Few moments make Iowa Wrestling Hall of Famer Dan Gable emotional: The birth of a grandchild. Reminiscing over family photos from when his daughters were younger.

The list gained entry one morning in October when Gable received a phone call from his son-in-law, Danny Olszta.

“He just said, ‘You better check your messages,’” Gable recalled.

Gable wasn’t sure what to expect, but he’s no stranger to big news, having been at the center of it for a quarter-century.

Gable, 72, was Iowa’s head wrestling coach for 21 seasons, from 1976 to 1997, and is the program’s all-time winningest coach. He collected 15 NCAA National Championships and racked up a career record of 355-21-5. Gable coached 152 All-Americans, 45 national champions, 106 Big Ten champions, and 12 Olympians—including four gold, one silver, and three bronze medalists.

As an athlete at fellow Regents’ university Iowa State, Gable held a career record of 181-1, graduating in 1970 as a three-time national champion. He won a 1971 world championship, and in 1972 he was an Olympic gold medalist, internationally recognized for not surrendering a single point during his championship run. He joined the University of Iowa wrestling staff the same year.

On Dec. 7, Gable receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House in Washington, D.C.; the award is the nation’s highest civilian honor, conferred upon those who have made especially meritorious contributions to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, culture, or other significant public or private endeavors.

It’s an award earned over a lifetime.

“It was one of those emotional times, and I was looking at a picture of my family and it broke me up,” Gable says of the call from the White House. “It’s one of these things that when I walk around the yard and talk to myself, I might cry a little bit.”

“It was one of those emotional times, and I was looking at a picture of my family and it broke me up. It’s one of these things that when I walk around the yard and talk to myself, I might cry a little bit.”

Dan Gable

Gable set the standard for wrestling at the University of Iowa, and his legacy is the foundation on which today’s program is built.

“Gable has left me a lifetime philosophy that I do not deviate from,” says Tom Brands, Iowa’s current head wrestling coach; he himself wrestled under Gable at Iowa from 1989 to 1992. “My brother and I are keen on the lessons we learned from him. That will never change. This award is awesome because it puts Dan Gable in context and brings him back front and center. Gable was a winner. He did not lose.”

Gable’s dedication to be the best echoes beyond wrestling and throughout Iowa athletics.

“He is known around the world and across all walks of life for his accomplishments in wrestling, but beyond that his incredible passion, focus, and his tenacious will to be the best,” says Henry B. and Patricia B. Tippie Director of Athletics Gary Barta. “There aren’t many people who can say they were the best in the world at what they did. Dan Gable can say that.”

Gable says he heard rumblings about possibly receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom over the last year, but he didn’t take it very seriously.

“I knew that this was in the works, but there are a lot of things that are in the works and never amount to anything. You kind of hang on it and live your life, but this was one of those markers in your life that you remember,” Gable says.

Gable will not only become the first wrestler or coach but the first member of the wrestling community at large to receive the honor, further cementing his status as a pioneer in the sport.

“This opens the door for the future of the sport,” Gable says. “I don’t know of any wrestler who has thought about receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, but now it can be a thought. Wrestling has been around forever, and this is important for our sport.”

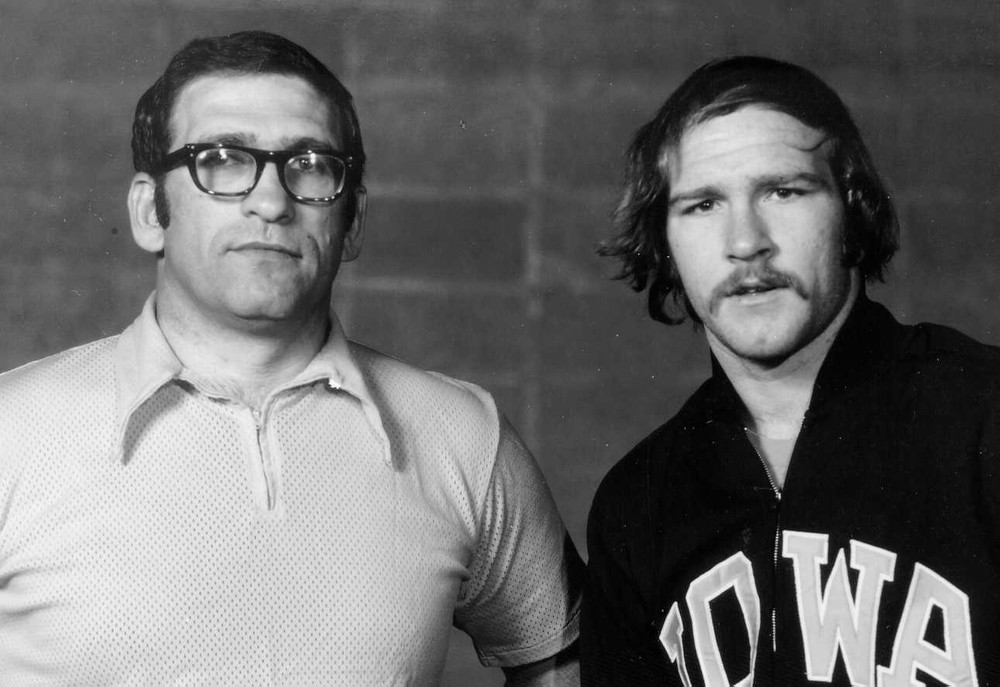

Gable continues to stump for wrestling in much the same way he did when he arrived at Iowa in 1972 as an assistant under fellow Iowa Wrestling Hall of Famer Gary Kurdelmeir.

“The University of Iowa brought me in and taught me,” he said.

Kurdelmeir took Gable under his wing and prepared him for a leading role at Iowa, which began four years later in 1976.

“He gave me the opportunities to learn about other aspects outside the wrestling room—it was so valuable,” Gable says. “Eventually, I got good at it.”

Iowa was not a top program during Gable’s early years, but with the right people in place, Hawkeye fans began to take notice.

“We took about 250 that came to a wrestling meet to 15,000 that came to a wrestling meet,” Gable says. “We used to bring everybody to college towns for these championships, but we don’t anymore because we’ve grown as a sport and we go to bigger arenas. It was a great thing for a place like Iowa City to have 20,000 people visit and stay for five days.”

The Iowa wrestling program served as a template for other Iowa teams to follow.

“It was a new program that showed others how to build a program,” Gable says. “It wasn’t simple, but you had the right people in place, including the athletic director, Bump Elliot; donors like Roy Carver; and the presidents of the university.”

Gable executed his vision of what he wanted Iowa’s program to be, and his legacy is embodied in a bronze statue outside Carver-Hawkeye Arena—fist out, calling his own student-athlete for stalling.

Though he left his head coaching duties in 1997, Gable has not wavered in his drive to advance and draw attention to the sport.

He wrestled competitively and coached competitively, and now he promotes competitively. A particularly notable example occurred seven years ago:

In 2013, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) voted to remove wrestling from its core games, effective in 2020. Gable played an instrumental role in the IOC reversing its decision seven months later, and included changes that modernized leadership structure, new rules for fans, and more opportunities for women’s wrestling.

Had he not remained intensely involved and dedicated, Gable says he doesn’t think he would be honored today.

“It’s hard to believe I only coached until I was 49 years old. I really haven’t let up with what I love and what I do. I don’t think I would have gotten this award if all the sudden I stopped in 1997,” he says. “It’s been 23 years and I am still doing things, and that won’t change.”