Hawkeye Fan Shop — A Black & Gold Store | 24 Hawkeyes to Watch 2018-19

By RICK BROWN

hawkeyesports.com

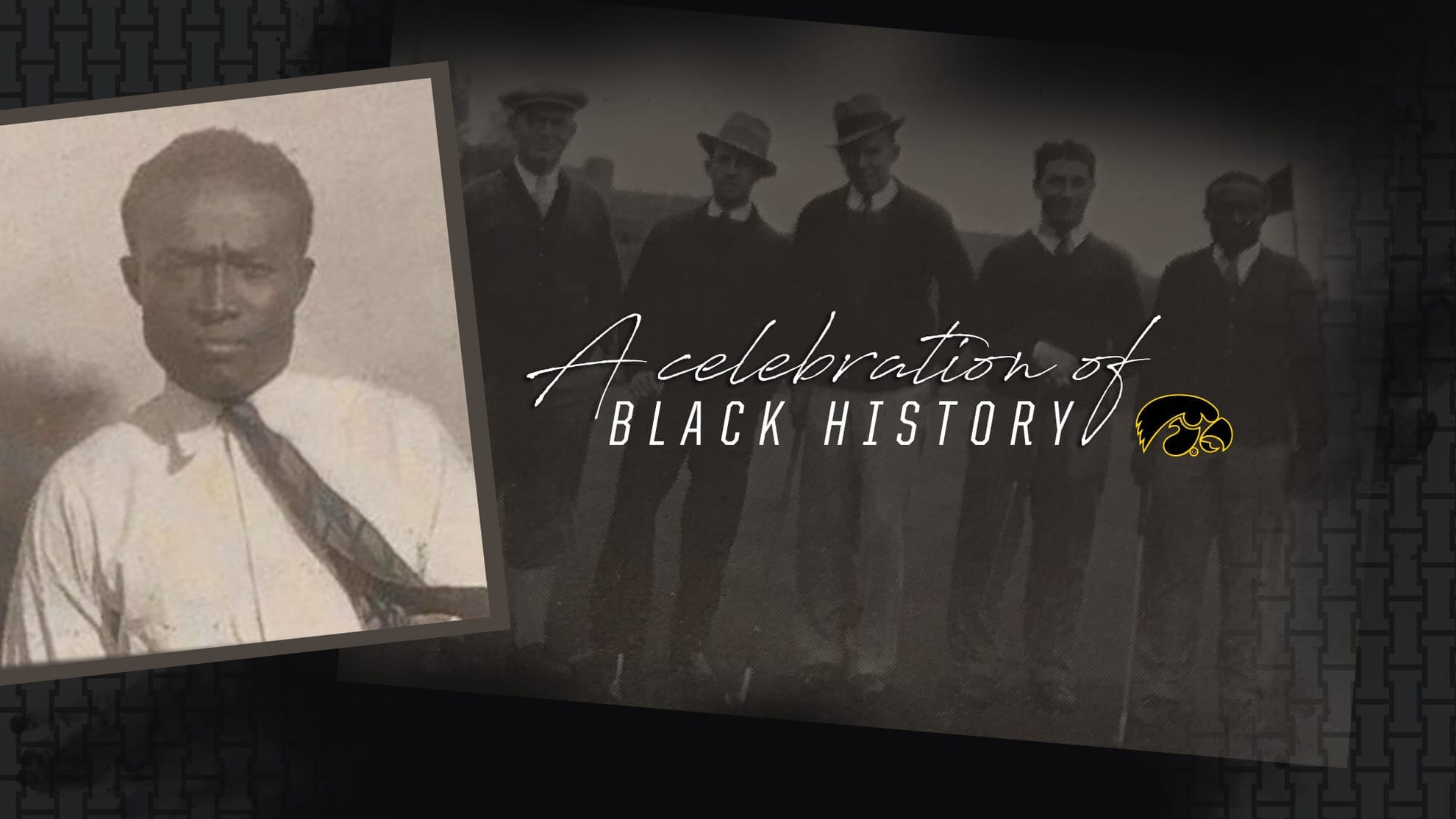

IOWA CITY, Iowa — George Roddy arrived at the University of Iowa with the Roaring ’20s winding down and the Great Depression on the doorstep.

His parents couldn’t afford bus fare to send him from their home in Keokuk, Iowa, to Iowa City. Legend has it that Roddy made the journey on foot. He took a suitcase and his golf clubs with him.

Roddy left with an engineering degree and a trailblazing legacy in 1931.

He was an outstanding golfer at the University of Iowa. He was the No. 1 man for the Hawkeyes in his final two seasons.

He was also the first African-American to play golf for Iowa and the color of his skin became as newsworthy as the impressive numbers he posted on his scorecard.

A May 24, 1929, story in the Iowa City Press-Citizen called him “George Roddy, colored sophomore from Keokuk.” The Des Moines Register labeled him “George Roddy of Keokuk, Negro star” on May 30, 1930.

When Roddy shot a course-record 72 at Finkbine in a dual with Minnesota on May 30, 1930, the first paragraph of the Press-Citizen story read, “George Roddy, Iowa’s colored golf star, came into his own at Finkbine Field Saturday.”

Roddy lettered in 1930 and 1931 and was also a team captain, but he never got a chance to play in a Big Ten Championship because of the color of his skin. Those championships were traditionally held at exclusive clubs that closed their doors to blacks.

Roddy didn’t crack Iowa’s varsity roster consistently in 1929, even though he was medalist in the varsity-freshman tournament to start the season. Roddy also won the All-University Championship that spring. He received the Rudolph A. Kuever Cup and the Howard L. Beye Traveling Trophy for his 2-and-1 victory over Marc Stewart in the championship match.

Coach Charles Kennett had Roddy at the top of his lineup when the 1930 spring season opened with a match against Grinnell.

“A star negro golfer from Keokuk, George Roddy, seems likely to head the attack against the Pioneers,” reported the Press-Citizen on April 15, 1930.

The Hawkeyes played just four matches in Roddy’s junior season. That’s because a football slush fund scandal prohibited Iowa from competing against other Big Ten schools. By the time a Big Ten faculty committee lifted that suspension in February of 1930, schedules were already set.

According to the 1930 University of Iowa yearbook, “The Hawkeye,”

“George Roddy repeated his performance of a year before when he outplayed all competition to win out in the all-university tournament in the spring. Roddy plays with a style that few teams could cope with and went through the season without once tasting defeat. In most cases he won his matches by quite comfortable margins. The late return of Iowa into the Western Conference accounted in part for the scheduling of but four matches.”

Iowa was able to add a dual with Minnesota in 1930 and Roddy took record-setting advantage of it.

His record 72 at Finkbine in May of 1930 was noteworthy for several reasons. It was a topsy-turvy 31-41 scorecard and he beat the Gophers’ William Fowler, the North Dakota Amateur champion of 1927 and 1929.

In addition to the defense of his All-University Championship, Roddy and teammate Fred Agnew went undefeated during the 1930 season for the Hawkeyes.

But neither made it to the first tee at the Big Ten Championships at Westmoreland Country Club in Wilmette, Illinois. Roddy wasn’t allowed to play because he was black. Agnew had a conflict with his senior law exams.

Jack Patton, the sports editor of the Press-Citizen, wrote on May 17, 1930, “Too bad about George Roddy and Fred Agnew not getting to take in the conference golf meet next week in Chicago. Agnew is busy with senior law exams, while Roddy’s color bars him from the Chicago links. Roddy wasn’t used at all last year in spite of his being all-university champ, and cut loose this year with three wins and a university course record. He’s Iowa’s most serious threat in conference golf history. No one has ever played on Finkbine field who has more golf etiquette than Roddy.”

Kennett took his skeleton team to Westmoreland Country Club, with predictable results. Iowa was last after the opening round, 44 shots behind ninth-place University of Chicago. Kennett pulled his team from the competition before the second round.

Roddy completed his eligibility in 1931. The highlight of the season was handing DePaul its first defeat in two seasons, 10-and-8. Roddy, who toured Finkbine in 73 shots, had a hand in six of those 10 points with victories in both his singles and doubles matches.

Roddy was denied a third All-University Championship in 1931, losing in the semifinals. Roddy did win the State University of Iowa team championship. The Hawkeyes also won the 1931 state collegiate championship. In his final competition as a Hawkeye, Roddy helped Iowa defeat visiting Iowa State, 11-7. He was not allowed to compete in meets at the University of Chicago or Northwestern because of the color of his skin.

“The Hawkeye team won three of its seven dual meets,” the Press-Citizen reported on May 19, 1931. “Absence of George Roddy, No. 1 man, weakened the team in the (University of) Chicago and Northwestern duals of last week. Roddy, a Negro, was barred from playing on the metropolitan club courses because of his color.”

With Roddy not available, Kennett elected not to enter the Big Ten meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

A week after receiving his degree from Iowa in July of 1931, Roddy went to Des Moines and won the inaugural Midwestern Negro Golf Tournament at Grandview. He also won the National Minority Amateur in 1930 and 1937.

Roddy went on to have an impressive career as an educator and coach. His first job out of college was at Arkansas State, where he worked as golf coach and instructor from 1931-33.

From there it was on to North Carolina A&T, where he was an auto mechanics, math instructor, and golf coach until 1948. His final stop was at Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis. In addition to working as an industrial arts teacher, Roddy started the school’s golf program.

And Roddy continued to play championship golf. He won the Indianapolis City title in 1963 and 1967. His second title came at 57 years of age. Roddy passed away in 1988 at 80 years of age. He became the first African-American elected to the Indiana Golf Hall of Fame in 1999.

%20--%3e%3csvg%20xmlns:inkpad='http://taptrix.com/inkpad/svg_extensions'%20height='231pt'%20xmlns:xlink='http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink'%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20width='796pt'%20version='1.1'%20viewBox='0,0,796,231'%3e%3cdefs/%3e%3cg%20id='Untitled'%20inkpad:layerName='Untitled'%3e%3cpath%20d='M102.252+48.3067L83.5399+48.3067L83.5399+182.202L102.252+182.202L102.252+230.822L-0.0490809+230.822L-0.0490809+182.202L18.6626+182.202L18.6626+48.3067L-0.0490809+48.3067L-0.0490809+0.300613L102.252+0.300613L102.252+48.3067ZM239.828+230.822L165.748+230.822C138.908+230.822+121.27+213.184+121.27+184.35L121.27+46.773C121.27+18.092+139.215+0.300602+165.748+0.300602L239.828+0.300602C266.669+0.300602+284.307+18.2454+284.307+46.773L284.307+184.35C284.307+213.031+266.362+230.822+239.828+230.822ZM218.816+182.356L218.816+48.4601L186.607+48.4601L186.607+182.356L218.816+182.356ZM313.448+48.3067L297.037+48.3067L297.037+0.300613L394.123+0.300613L394.123+48.6135L375.718+48.6135L392.282+159.503L426.945+0.300613L476.025+0.300613L512.834+159.503L526.178+48.6135L509.307+48.6135L509.307+0.300613L605.166+0.300613L605.166+48.6135L589.368+48.6135L560.534+231.129L482.313+231.129L451.945+95.0859L420.963+230.822L345.81+230.822L313.448+48.3067ZM588.141+182.356L605.779+182.356L640.902+0.300613L745.656+0.300613L780.166+182.356L796.577+182.356L796.577+230.975L718.356+230.975L710.994+174.687L672.19+174.687L665.288+230.975L588.601+230.975L588.141+182.356L588.141+182.356ZM706.853+132.509L691.975+39.4111L676.638+132.509L706.853+132.509Z'%20opacity='1'%20fill='%23ffcd00'/%3e%3c/g%3e%3c/svg%3e)